“Stand Up and Speak to It”: Learning from the Historical Legacies of Bay Area Black Teachers

In 1964, Ms. E Toney Williams attended the Third Baptist Church of San Francisco on Sundays. As soon as the service ended, she’d march down Van Ness Avenue in high heels and Sunday best with her late husband, Benjamin Rubin. The San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) central office sits at 135 Van Ness, and Mrs. Williams recalls that “when the [Black] churches emptied on Sunday, we knew where we were going to meet: Van Ness.” Armed with picket signs or just fiery words, they’d march for school integration.

On this 70th anniversary of the 1954 Supreme Court ruling that mandated school integration, Brown v. Board of Education, we look to this historical moment when Bay Area Black educators joined teachers from across the country to fight racism in the form of school segregation. We must remember that not all its outcomes were positive: Before 1950, almost half of all professional Black women were educators, yet one result of the Brown decision was that thousands of Black teachers lost their jobs. While many rejoiced when Brown deemed “separate but equal” illegal, the teeth required to enforce the new law was delayed until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

It wasn’t until 17 years after the Brown decision, for example, that San Francisco was legally compelled to desegregate SFUSD’s schools. In 1971, Johnson v. SFUSD was the first court-mandated segregation case outside the South. And yet, as Black education researchers and former K-12 educators interested in the history of education, when we began researching the history of Johnson’s implementation here, we had difficulty finding firsthand accounts of Black teachers in the Bay Area between 1969 and 1979.

We focused on oral history to elevate Black educators' wisdom and lived experiences in the Bay Area. Sitting in living rooms, offices, and backyards, we spoke to a dozen veteran Black teachers. We chose educators who taught during the 1960s and 1970s, a time fraught with battles over busing, curriculum, and desegregation in the Bay Area. We learned what led them to enter the teaching field and how they navigated the challenges of teaching in tumultuous times. What emerged from these conversations were lessons that are as applicable today as they were when these women first entered the classroom decades ago:

Stay focused on the children. Mrs. Lucretia-del Broussard tells us it was “challenging to stay focused on mental health and not get too angry” as she faced racial comments from coworkers and community members. How do we do that? Focus on the children. Dr. Bettye Haysbert created a nurturing learning environment in her classroom, making it a sanctuary from outside chaos. Mrs. Bessie Stewart-Ross set motivating and concrete goals for herself: No child would leave her class without being able to read.

Sit at the metaphorical lunch table. Broussard started her career in Stockton, CA, at a school where she was the only Black teacher. When white teachers refused to sit at her lunch table, she sat there day after day instead of eating in her classroom. She “refused to be intimidated.” She wanted to be seen. Finally, months later, a newly hired, young, white woman teacher sat down with her one day and initiated a conversation. Mrs. Broussard warned her about the consequences of doing so, but the teacher said she didn’t care. Whether pioneering or supporting change, it’s important to be at the right lunch table.

- “Stand up and Speak to It.” Colonel Dr. Shirley Thornton described the racial unrest at Aptos Middle School during integration, telling us that she’d often get pulled from her P.E. classroom to break up fights. When Thorton asked why she couldn’t become a school counselor, a principal told her she'd never be an administrator in the district because she talked back. “If something wasn’t right, I was going to stand up and speak to it,” Thornton says. Not only did Dr. Thornton eventually become a counselor, but she was also chosen as California’s Deputy Superintendent with Specialized Programs, all while continuing to “talk back” to antiblackness. Other teachers addressed important topics deemed too taboo to teach, like Japanese internment camps or the AIDs epidemic. They stayed true to themselves and did what they felt was right for students.

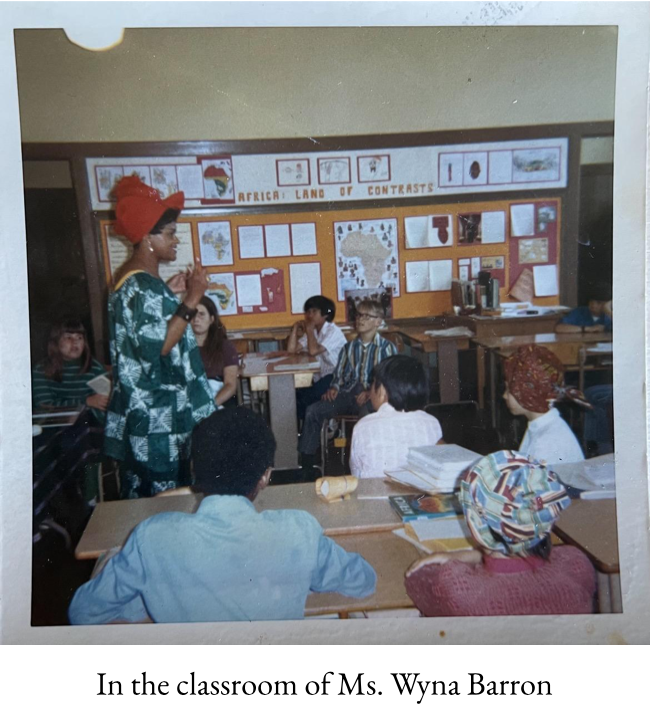

As we think about how to recruit and retain Black educators in the Bay Area, the perspective of veteran Black teachers like Ms. Barron, Mr. and Mrs. Render, Ms. Threadgill, Dr. Delane, and Dr. Marshall is an invaluable asset and one that needs to be made part of the conversation. Teachers can learn from how these women brought their whole selves into the classroom to serve their students, navigated institutions that were often openly anti-Black and unwelcoming, and forged sustaining interpersonal networks that allowed them to persist in the profession for decades. We need this historical knowledge more than ever, as history is beginning to repeat itself with school segregation on the rise. Policymakers, teacher educators, and administrators should listen to these voices to better grasp the underlying conditions: low pay, hostile work environments, and the lack of intentional opportunities to build community among them, which led many Black teachers to leave the classroom. Letting one generation of educators speak to the next can strengthen the field and ensure that past educators' legacies and lessons inform our present and future. As Oakland-based The Black Teacher Project nonprofit asserts, “Every child deserves a Black teacher.”