Techno-optimism, school surveillance, and GoGuardian

“The extent to which I’m able to control is often the extent which I’m able to observe”

This was the sentiment one teacher shared in April 2024 during a sequence of interviews about AI, language, and cheating in the classroom.

Surveillance is crucial to education. Teachers must monitor students by observing the classroom and grading their assignments to provide formative and summative feedback. However, with new educational technologies, the capacity for observation that’s possible has greatly increased, along with the capacities for sharing and analyzing student data. And the purposes of surveillance have shifted, with a growing emphasis on detecting or predicting which students are “at-risk” or may be a risk to others.

Many companies offer monitoring tools to districts. Their products generally promise to mitigate issues related to mental health, cheating, and classroom management. But, while schools and districts may accept such assurances, students often evade or resist the tools in subversive ways. Moreover, the slow creep of surveillance software may begin to reshape how we think about privacy and student rights.

These developments are fascist because they erode student privacy to a historically unprecedented degree and they complicate the pursuit of equitable education by enabling a more surgical criminalization of marginalized youth. One tool which exemplifies many of these trends is GoGuardian, a software that allows teachers and district administrators to monitor students’ browsing activity.

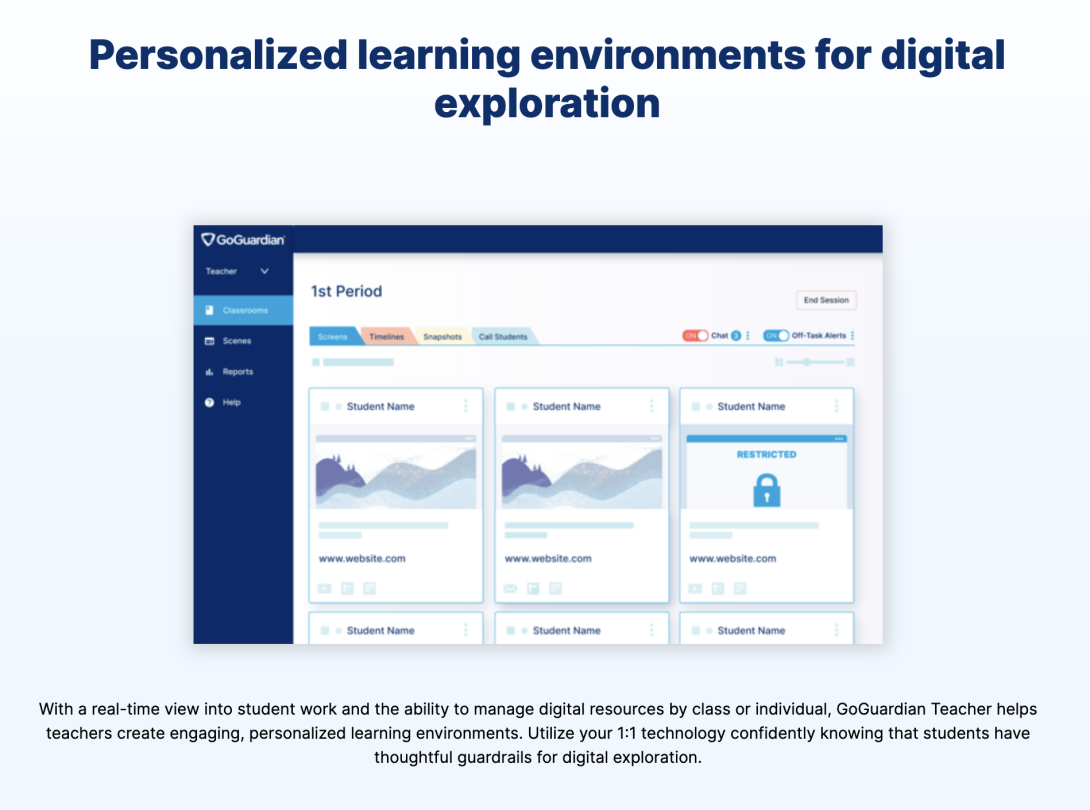

GoGuardian describes itself as a software to empower K-12 leaders and create “safe and engaging learning for every student.” It’s a tool that schools can install on student computers which can log their browsing history, location, apps/extensions, and more. The tool streams a view of each student’s monitor to the teacher, which the company has framed as enabling “personalized learning,” a trendy catchphrase in education technology that reflects an educational philosophy which favors a neoliberal containment of individualism over the capacity of students to be in community with one another. The software also assigns a mental health “risk score” to each student that is meant to capture the likelihood they will commit a crime or harm themselves. Similar metrics in the criminal legal context have been widely criticized as a violation of civil liberties and as a modern form of eugenics because of their reliance on spurious correlations rather than meaningful understandings of health and crime.

Despite the criticism, GoGuardian and tools like it have been widely adopted in education with 89% of US-based teachers reporting that their districts use some kind of monitoring software for student devices. This leaves educators in a challenging position, often forced to choose between fraught monitoring tools and a seemingly less manageable school environment. However, decades of educational research has identified techniques for addressing many of the underlying concerns that teachers, districts, and regulatory agencies turn to GoGuardian to address.

Alternatives to GoGuardian monitoring

Rather than track students with GoGuardian and use the results to make predictions about their mental health, teachers and districts should ask: What is the deeper issue we’re trying to address?

- Teachers are often worried about cheating and see GoGuardian as a way to address that because they can tell what students are doing during work time. Be aware that using this tool can have a serious impact on the structure of the classroom, turning teachers into dashboard-watchers and intimidating students. Research suggests that a more caring climate, with reasonable demands on student time and an emphasis on learning rather than performance, is a deeper way to address this problem.

- Districts are often concerned about safety but these tools are, at best, spuriously predictive. Safety concerns must be understood as part of a context in which the work of school counselors is undervalued—48 of 50 states are above the recommended student to counselor ratio of 250:1—and it can seem cheaper to use software like GoGuardian than hire more counselors. That calculation is misleading as GoGuardian can raise more than 50,000 flags per day for some large districts, leaving administrators to comb through the data themselves, a hidden cost that often might not be factored into the decision to purchase the software. More counselors and a climate of trust is a more effective way to address these concerns.

- Regulatory and professional agencies like COSN are typically concerned about preserving student privacy while allowing for innovation. Although privacy frameworks have generally focused on student data retention and sharing, the algorithmic predictions are also a kind of privacy intrusion. Not only is it deeply intimate to label someone as mentally languishing but such a label, when it’s issued by GoGuardian, could bring those students into contact with even more intrusive systems like CPS or police which can further threaten their right to privacy. Regulatory agencies should develop, promulgate, and audit policies to ensure that these technologies are healthier, narrower, and more in line with scientifically-supported evidence about mental health.

Inequities in implementation

Although GoGuardian purports to be aligned with progressive values, it can create a culture of mistrust and intimidation while lending administrators the appearance of objectivity when they make carceral decisions. Schools can retain logs of student data for long periods of time and studies have found that those logs tend to be used retrospectively and mostly for disciplinary purposes rather than to refer students for mental health care. Moreover, data breaches are a real threat to schools. So GoGuardian and tools like it make it easier for administrators to harm marginalized students and dig up evidence that justifies those practices, whether or not the student has done anything wrong.

For example, in Minneapolis, a student’s search results included the word “queer” and the search was flagged by Gaggle, a software similar to GoGuardian. School administrators got in touch with the student’s parents to discuss and, in so doing, outed the kid to their parents. Of course, browsing history that includes “queer” is not an indicator of queerness or deviancy, but the administrators decided it warranted a call home. This story reflects a pattern: Queer students are disproportionately targeted using monitoring tools and often in ways that lead to the nonconsensual disclosure of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

As another example, GoGuardian has partnered with the AI company Databricks and now sends “all the datathey ingest from their business systems to Databricks Data Intelligence Platform” with the goal of improving AI algorithms for “suicide and self-harm prevention.” (GoGuradian claims to remove all personally identifiable information, but research has identified the risks of to re-identify data, especially when it is collected robustly over an extended period of time.) But, AI algorithms have been shown to mark speech from non-standard dialects of English as deviant: One study found that data workers tend to label tweets using the n-word as toxic (even if they were written by a Black author) which is then reproduced by AI models trained on those data. As GoGuardian “improves” by adopting AI, it will likely get better at targeting Black and brown students by overpenalizing browsing history that includes words from their dialects and languages.

These tools are intensifying the criminalization of minoritized students at a time when identity-based attacks on the same students are also intensifying in the US and worldwide. The teaching of gender and critical race theory is being disavowed or banned as a form of “indoctrination.” US border policies have become more punitive as right-wing politicians invoke white supremacist rhetoric about immigrants. Pregnant people are less able to make decisions about their bodies and prosecutors have begun using browsing history as evidence in cases against abortion providers and patients.

In this climate, monitoring tools can threaten a student’s privacy over their gender or immigration status or pregnancy or queerness. The tools have been shown to cause more stress and languishing, the very issues they are intended to solve. While the benefits of GoGuardian are dubious, we do know it has very real harms because these tools are markers of non-normativity and expedite the regulation and policing of Black and brown bodies.

Teachers and districts should resist these tools in the same way they resist normative and carceral approaches to education. Not only are tracking tools largely ineffective, they break with historically accepted levels of surveillance in schools because they are much more invasive and much less useful than other forms of school surveillance.

The companies who promote tools like GoGuardian are incredibly good at marketing and playing to the sensitivities of schools and districts. One teacher in our research study said they have to monitor their students because, if a student cheats, they need evidence: “Parents will not believe anything unless there’s evidence,” they said, adding, “so I’m sitting here like, well, I guess I have to do this.” Amanda Peskin has offered a sympathetic note to schools saying they’re “caught in a catch-22 of sorts where they will either be blamed for school shootings if they refrain from surveilling their students or criticized by students, parents, advocacy groups, and other interested parties if they deploy surveillance technology.” These algorithms can provide a convenient scapegoat for teachers, schools, and districts that are worried about cheating, violence, or mental health risks, even if they don’t actually help.

Student crime, mistrust between teachers and parents, and the political concerns of district officials reflect deep, systemic, relational issues with the fraught systems of public education. While it promises to solve them, GoGuardian and tools like it introduce many more problems. A healthier response begins with realizing that a culture of languishing, mistrust, and stress among students lies at the heart of many of these issues. That culture will only be made worse by introducing tracking tools but, in solidarity with one another, students, teachers, families, and administrators can craft a more livable world.

Header photo by ROBIN WORRALL on Unsplash

Software screenshot by authors